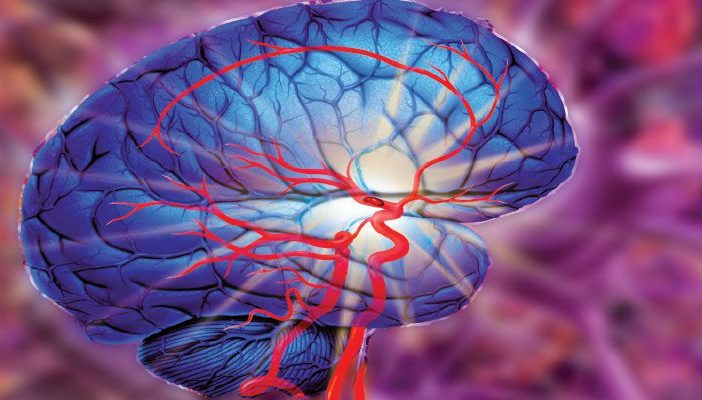

Scientists at the University of California, Davis developed vascularized human neural organoids opening up new possibilities in the development of neural networks

Ben Waldau, a vascular neurosurgeon at UC Davis Medical Center and colleagues isolated brain membrane cells from patients and then coaxed some of them into stem cells. The stem cells they grew into brain balls, which they incubated in a gel matrix coated with endothelial cells. “The whole idea with these organoids is to one day be able to develop a brain structure the patient has lost made with the patient’s own cells,” said Waldau. “We see the injuries still there on the CT scans, but there’s nothing we can do. So many of them are left behind with permanent neural deficits—paralysis, numbness, weakness—even after surgery and physical therapy.”

The cell spheres matured into 3D structures, fusing with other types of brain balls and sparking with electricity. The have applications in studying complex behaviors and neurological diseases beyond the reach of animal models. After incubating for three weeks, they took a single organoid and transplanted it into a tiny cavity carefully carved into a mouse’s brain. Two weeks later the organoid were functional with functional capillaries that penetrated to its inner layers.

Furthermore, blood supply carries oxygen and nutrients, allowing brain balls to grow bigger, complex networks of tissues, those that a doctor could someday use to shore up malfunctioning neurons. Moreover, Salk Institute and the University of Pennsylvania have successfully transplanted human organoids into the brains of mice, but in both cases, blood vessels from the rodent host spontaneously grew into the transplanted tissue.